When to Fight to Keep People (And When to Let Them Go)

Most companies fight to keep everyone. The best fight to keep the right people.

There’s a moment every manager dreads. Your best engineer walks into your office and says she’s got an offer from a competitor. Or your top sales rep mentions he’s “exploring options.” Or your operations lead - the one who knows every process, every customer quirk, every workaround that keeps things running - casually drops that a recruiter has been calling.

Your immediate reaction is probably some version of panic. You start calculating: How long would it take to replace them? What would it cost to recruit someone new? How much institutional knowledge would walk out the door? What would happen to the team’s morale? And within about thirty seconds, you’ve convinced yourself that you need to do whatever it takes to keep this person. You start thinking about counteroffers. Salary bumps. Title changes. Special accommodations. Whatever they want, you’ll figure it out.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: this panic-driven approach to retention is often exactly wrong.

Not because you shouldn’t fight to keep great people - you absolutely should. But because the decision about when to fight and when to let someone go shouldn’t be made in a moment of panic with incomplete information and no framework for thinking through the tradeoffs. Most managers operate on pure instinct when it comes to retention decisions: keep the people you like, accept that others will leave, react to offers when they materialize, hope for the best. There’s no systematic thinking about which retention battles are worth fighting, which exits actually help your organization, or what the real economics look like.

The result? Companies overpay to retain mediocre performers who have leverage, while simultaneously losing exceptional people they could have kept with relatively modest investments. They negotiate desperate counteroffers with employees who have already mentally checked out, burning goodwill and budget on retention attempts that fail six months later anyway. They treat all turnover as equally bad, failing to distinguish between regrettable losses and addition-by-subtraction exits.

Here’s what great operators understand: retention is not a binary choice between keeping everyone or accepting high turnover. It’s an optimization problem. The goal isn’t minimizing turnover. The goal is maximizing the return on your retention investments - being strategic about which people you fight to keep, which exits you facilitate gracefully, and which situations require difficult conversations about fit.

This is Retention Economics: a framework for thinking systematically about when retention investments pay off and when letting people go is actually the right move for both the organization and the individual.

Understanding the Retention ROI Model

Let’s start by making explicit what most managers calculate intuitively but imprecisely. Every retention decision is fundamentally an economic tradeoff between two scenarios:

Scenario A: Keep the person (with whatever it takes to retain them)

Scenario B: Let them go (and deal with replacement)

The question is: which scenario creates more value after accounting for all costs?

The Basic Retention ROI Formula

Retention ROI = (Future Value of Employee) - (Cost to Retain)

Compare to:

Replacement ROI = (Future Value of Replacement) - (Total Replacement Cost + Transition Cost)

Decision Rule:

If Retention ROI > Replacement ROI → Fight to keep them

If Replacement ROI > Retention ROI → Let them go (gracefully)

Simple in principle. Complex in practice because each variable requires judgment and estimation. Let’s unpack what goes into each component.

Future Value of Employee (If You Keep Them)

This isn’t just “how good are they now?” It’s a forward-looking assessment of what value they’ll create over the next 2-3 years if they stay. Consider:

Current Productivity Level:

Are they in the top 20% of performers? Middle 60%? Bottom 20%?

How does their output compare to team average?

What’s their quality level (defects, rework, customer satisfaction)?

Growth Trajectory:

Are they improving, plateauing, or declining?

How much upside is left in their development?

Are they learning new skills or coasting on what they know?

Institutional Knowledge Value:

Do they hold critical information that’s hard to transfer?

Are they the only person who knows certain systems/relationships?

How proprietary is their knowledge vs. industry-standard skills?

Cultural Impact:

Do they raise or lower the performance bar for others?

Are they mentoring/developing other team members?

Do they amplify or drain team energy?

Team Dynamics:

How dependent are others on them?

Would losing them create a cascade of other exits?

Or would their exit actually improve team function?

The future value calculation gets tricky because you’re trying to predict not just what they’ll produce, but also what they’ll cost in terms of management time, coordination overhead, and cultural impact. A high-output person who creates political drama might have negative net value despite strong individual metrics.

Cost to Retain

What will it actually take to keep this person, and what are you giving up by spending those resources here instead of elsewhere?

Direct Compensation Adjustments:

Salary increase needed to match or beat outside offer

Bonus or equity grants to create golden handcuffs

Premium over market rate to make them feel valued

Indirect Costs and Accommodations:

Title promotion (creates salary compression issues with others)

Remote work flexibility (if it’s an exception to team policy)

Special project assignments (opportunity cost of not giving those to others)

Reduced workload or responsibilities (someone else absorbs them)

Opportunity Cost:

That $20K raise could have gone to three high-performers as merit increases

That VP title creates expectations from others who’ve been here longer

That remote exception becomes a precedent you’ll have to defend

Future Retention Costs:

If you cave to pressure now, you’ve signaled that threatening to leave works

Next negotiation will start from this new baseline

Other team members may use this playbook

The cost isn’t just the immediate financial hit. It’s the precedent you’re setting, the expectations you’re creating, and the resources you’re deploying here instead of investing in other team members who haven’t threatened to leave.

Total Replacement Cost

If you let them go, what does it actually cost to get back to equivalent productivity with someone new?

Direct Recruiting Costs:

Agency fees (typically 20-30% of first-year salary)

Internal recruiter time

Job board postings, marketing

Interview time from hiring manager and team

Onboarding and Training Costs:

HR onboarding administrative time

Manager time getting them up to speed

Team member time doing knowledge transfer

Training programs, certifications, tools

Productivity Ramp Time:

Junior roles: 3-6 months to full productivity

Mid-level roles: 6-9 months

Senior/specialized roles: 9-18 months

During ramp, they’re producing <100% while consuming >100% of management time

Productivity Gap During Search:

Time from resignation notice to new hire start date

Remaining team members absorb the work (overtime, delayed projects)

Opportunities missed because capacity wasn’t available

Risk Costs:

What if the replacement doesn’t work out? (30-40% of hires don’t make it past year one)

What if the search takes 3 months longer than expected?

What if market rates have risen and you’re priced out of good candidates?

The Math by Role Level:

Junior roles (individual contributors, <2 years experience):

Replacement cost: 50-75% of annual salary

Ramp time: 3-6 months

Mid-level roles (experienced ICs, first-time managers):

Replacement cost: 100-150% of annual salary

Ramp time: 6-9 months

• Senior roles (senior ICs, experienced managers, specialized experts):

Replacement cost: 200-400% of annual salary

Ramp time: 9-18 months

These aren’t small numbers. A $100K mid-level employee who leaves costs you $100K-150K to replace. A $150K senior person costs $300K-600K when you add up all the components. This is why the instinct to “do whatever it takes to keep them” often makes sense - replacement is genuinely expensive.

But here’s the critical question: what’s the future value of the replacement compared to the person who’s leaving?

Future Value of Replacement

This is where most retention calculations go wrong. Managers compare the cost of retention to the cost of replacement, but forget to factor in that the replacement might actually be better.

If the person threatening to leave is a B-player, and you can recruit an A-player as their replacement, the math changes dramatically. The replacement cost is high, yes, but the future value delta is enormous.

Consider:

Upgrading performance: Moving from 50th percentile to 75th percentile performance means 30-50% more output from that seat

Resetting compensation: New hire starts at market rate, not inflated retention rate

Cultural refresh: New person brings outside perspective, challenges assumptions, introduces new approaches

Team dynamics reset: Opportunity to eliminate dysfunction that had calcified around the existing person

The counterintuitive insight: sometimes the best retention strategy is letting people go and upgrading the replacement.

Transition and Exit Costs

But there’s one more variable: what does the actual transition cost you?

Direct Exit Costs:

Severance (if you’re initiating the exit)

Accrued PTO payout

COBRA/benefits continuation

Exit interview time

Knowledge Transfer Costs:

Documentation of processes/relationships

Handoff meetings with team

Manager time overseeing transition

Risk of information loss despite best efforts

Team Morale Impact:

Do remaining team members see this as losing a valued colleague?

Or as removing someone who was dragging things down?

Does this create retention risk with others?

Or does it send a positive signal about performance standards?

Customer/Stakeholder Impact:

Are there relationships that might be disrupted?

Will customers/partners need reassurance?

Is there contract/project continuity risk?

The transition costs vary wildly depending on role, performance level, and how you handle the exit. A graceful, well-managed exit of a wrong-fit employee can actually improve team morale and send positive cultural signals. A botched exit of a valued performer can trigger a cascade of other departures.

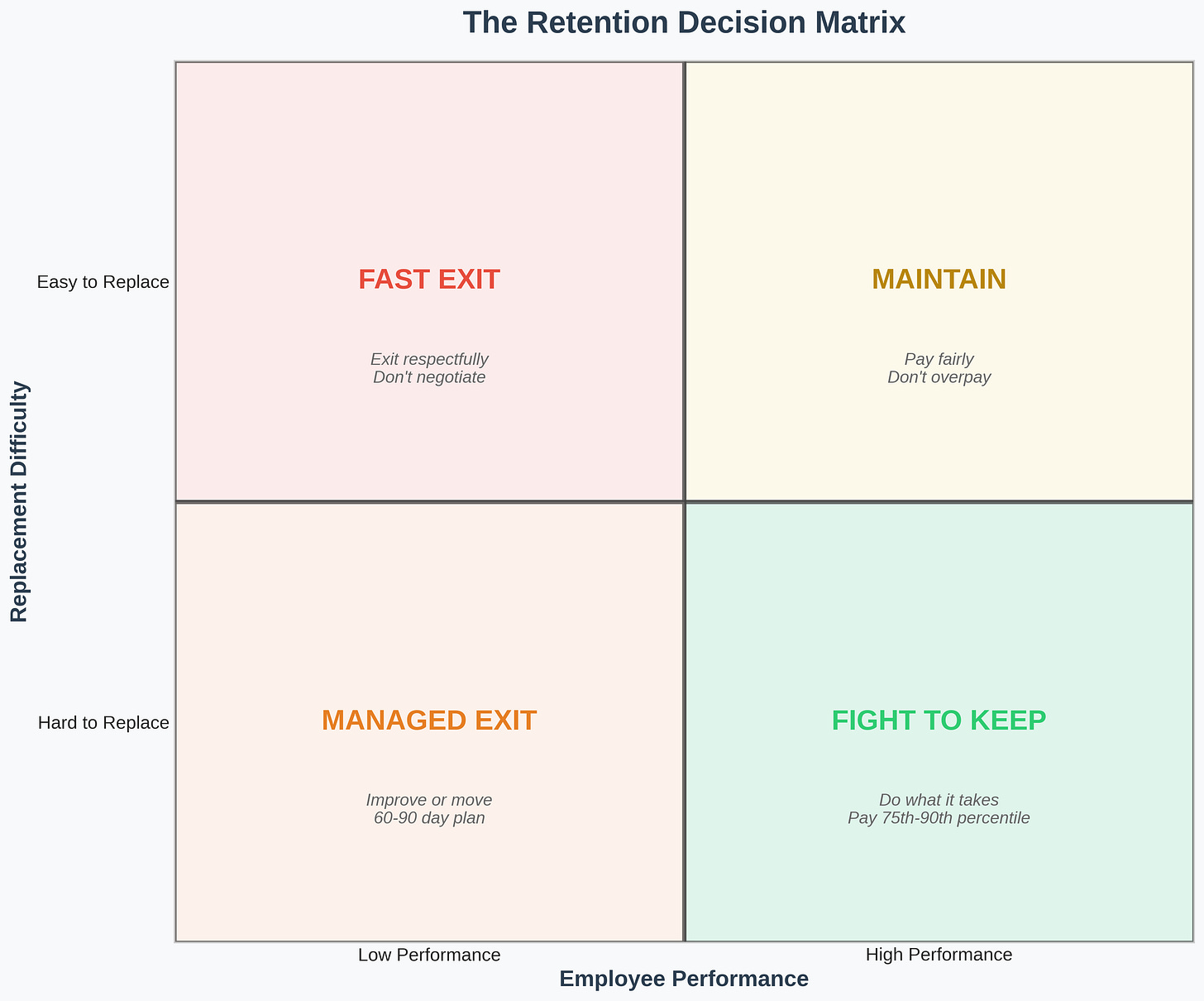

The Retention Decision Matrix

Now that we understand the variables, let’s build a systematic framework for making retention decisions. The two key factors that determine your strategy:

X-axis: Employee Performance (Low → High)

How valuable is this person’s current and future contribution?

Y-axis: Replacement Difficulty (Easy → Hard)

How hard would it be to find an equally good or better replacement?

This creates four quadrants, each requiring a different retention approach.

Quadrant 1: High Performance + Easy Replacement

Strategy: MAINTAIN (Don’t overpay)

These are good performers in roles where the talent market is deep. Think: solid mid-level engineers in major tech hubs, competent sales reps in established territories, capable operations managers in common industries.

What to do:

Pay at 50th-75th percentile of market

Provide good (not exceptional) development opportunities

Appreciate their contribution but don’t create golden handcuffs

If they get a better offer, match within reason but don’t go crazy

What NOT to do:

Don’t overpay to retain at all costs

Don’t promote them just because they threatened to leave

Don’t create special accommodations that become precedents

Why this works:

If they leave, you can replace them relatively easily with someone of similar quality. Fighting too hard to keep them often means overpaying for replaceable talent, which creates salary compression issues and sets bad precedents.

Quadrant 2: High Performance + Hard Replacement

Strategy: FIGHT TO KEEP (Do what it takes)

These are your exceptional performers in specialized roles or tight labor markets. Top 10% engineers with rare skills, rainmaker sales leaders with major client relationships, operations experts with deep institutional knowledge in complex environments.

What to do:

Pay at 75th-90th percentile (or higher for truly exceptional)

Create strong golden handcuffs (equity, retention bonuses)

Provide exceptional development and growth opportunities

Give them interesting projects and high autonomy

Match or beat any reasonable outside offer

Have proactive retention conversations quarterly

What NOT to do:

Don’t wait until they have an offer to invest in retention

Don’t assume loyalty means you can underpay

Don’t ignore signs of disengagement

Why this works:

The replacement cost is enormous (18+ months of productivity gap, 200-400% of salary in hard costs), the risk of not finding an equal replacement is high, and the future value delta is massive. Overpaying to keep them is often cheaper than the replacement scenario.

Quadrant 3: Low Performance + Easy Replacement

Strategy: FAST EXIT (Don’t negotiate)

These are underperformers in roles where replacements are readily available. Bottom 20% performers in common roles, wrong-fit hires, people who’ve plateaued well below where the role needs to be.

What to do:

Exit them respectfully but decisively

Generous severance (6-8 weeks per year of service)

Clear, honest feedback about fit

Help with job search if appropriate

Fast, clean execution

What NOT to do:

Don’t negotiate or create retention packages

Don’t delay hoping they’ll magically improve

Don’t create performance improvement plans that drag on for months

Why this works:

Keeping them is expensive (low productivity, high management time, negative team impact). Replacing them is relatively easy and often yields a significant upgrade. The ROI on retention is deeply negative.

Quadrant 4: Low Performance + Hard Replacement

Strategy: MANAGED EXIT (Coach Up/Coach Out - Improve or move)

These are underperformers in specialized roles where replacements are hard to find. Someone with rare skills who isn’t performing well, or someone in a niche role where the talent pool is thin.

What to do:

Give them one real chance to improve (60-90 days, clear metrics)

Provide coaching and resources

If no improvement, help them transition to a better-fit role (internal or external)

If they leave voluntarily, accept it and invest in the search

Consider restructuring the role or building internal pipeline

What NOT to do:

Don’t keep them indefinitely because “we can’t find anyone else”

Don’t lower standards just because replacement is hard

Don’t create a retention package for someone who’s not performing

Why this works:

You give them a real shot to improve (sometimes people in the wrong role can thrive with the right support). If they can’t improve, you transition them out despite the replacement difficulty, because keeping a low performer in a critical role is worse than having a temporary gap.

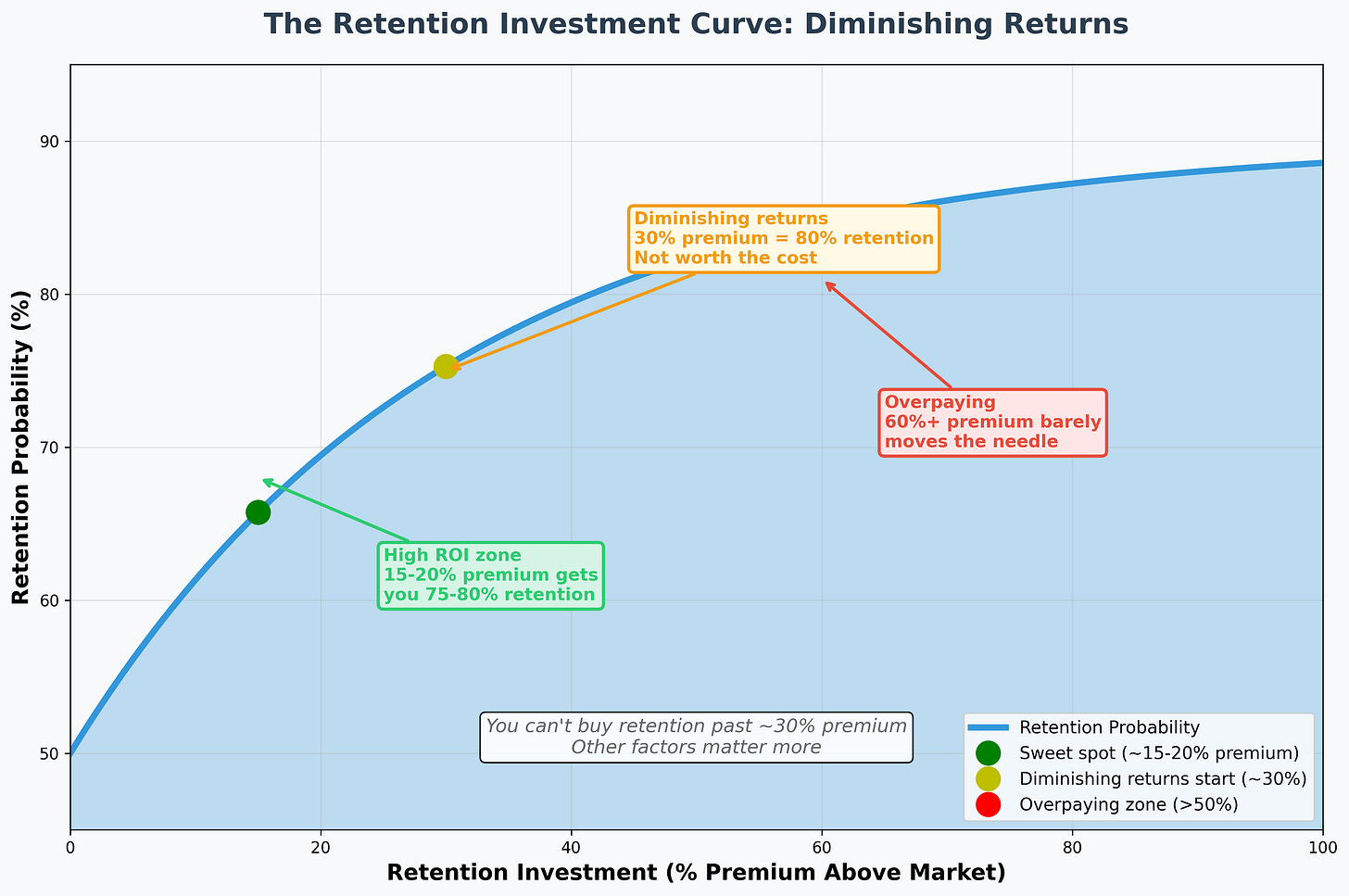

When Retention Investments Pay Off

Now that we have the decision matrix, let’s get more specific about when fighting to keep someone actually creates positive ROI. There are patterns here that hold across industries and roles.

Pattern 1: Top 20% Performers (Almost Always Worth It)

If someone is genuinely in the top 20% of performers - not just “pretty good” but actually exceptional relative to peers - the retention math almost always works in your favor.

Why? Because the productivity variance is so large. Remember from the Talent Density framework: top performers often produce 2-5x more than average performers. That means:

A top engineer at $150K is cheaper than three average engineers at $100K each ($150K vs. $300K)

A top sales rep at $200K who closes $5M is cheaper than two average reps at $150K who each close $2M (higher revenue, lower cost)

A top operations manager at $120K who runs a 50-person team efficiently is cheaper than two average managers at $90K who struggle with 25 people each

The retention strategy for top 20% performers:

Pay them 75th-90th percentile (minimum) - they’re worth it

Create golden handcuffs - equity that vests relatively quickly, retention bonuses that pay out annually

Give them the interesting work - your best people want to work on hard, important problems

Invest in their development - conferences, coaching, stretch assignments

Have quarterly retention conversations - don’t wait for an offer to check in

What this costs vs. what you save:

Cost to retain top performer: $30K-50K/year premium over average

Cost to replace top performer: $200K-400K one-time + 12-18 month productivity gap

Break-even: If they stay 2+ years, retention investment pays for itself many times over

Pattern 2: Specialized Skills in Tight Labor Markets

Even if someone is just a solid performer (not top 20%), if they have genuinely rare skills and the talent market is tight, retention often makes sense.

Examples:

AI/ML engineers (limited supply, massive demand)

Healthcare specialists in rural areas (geographic constraints)

Regulatory compliance experts in niche industries (small talent pool)

Skilled tradespeople during labor shortages (cyclical supply/demand)

Why replacement is expensive:

6-12 month searches (opportunity cost of work not getting done)

Premium salaries (supply/demand means you’ll pay more for replacement than retention)

Geographic constraints (may need to relocate someone, which is expensive)

Training time (specialized skills take longer to ramp)

The retention strategy:

Pay at market or slightly above (market moves fast in tight talent pools)

Focus on non-comp retention levers: remote flexibility, interesting projects, autonomy

Build internal pipeline so you’re not perpetually vulnerable (train/develop others)

Accept that some turnover is inevitable - don’t overpay just because of scarcity

Pattern 3: High Institutional Knowledge Roles

Some people hold knowledge that’s genuinely hard to transfer - not because the knowledge itself is complex, but because it’s tacit, distributed across relationships, or embedded in systems that aren’t well-documented.

Examples:

Key account managers with 10-year client relationships

Long-tenured engineers who understand legacy systems

Operations managers who know all the informal workarounds

Finance people who understand the history behind current structures

When institutional knowledge actually matters:

The knowledge is genuinely hard to document (relationship-based, tacit)

Losing it would create real operational or revenue risk

No one else on the team has meaningful overlap

The time to rebuild the knowledge is >12 months

When institutional knowledge is overrated:

The knowledge is documentable but hasn’t been (that’s a process problem, not a retention issue)

Only one person knows it because of information hoarding (that’s a cultural problem)

The knowledge is about legacy systems that should be deprecated anyway

The retention strategy:

Pay fairly but don’t overpay just because they “know everything”

Simultaneously invest in knowledge transfer and documentation

Cross-train others to reduce single-point-of-failure risk

If they leave, treat it as a forcing function to improve systems and documentation

Pattern 4: Cultural Carriers and Mentors

Some people create value not just through their individual output but through their impact on others. They raise the performance bar, they mentor junior team members, they model the culture you’re trying to build.

Characteristics of cultural carriers:

Other team members actively seek their advice and mentorship

New hires ramp faster when paired with them

They give candid feedback that improves team performance

They attract other strong performers (people want to work with them)

They embody the values you’re trying to reinforce

Why they’re worth retaining even if individual output is only above-average:

They have a multiplier effect on team productivity

Losing them can trigger other exits (people came to work with them)

They’re hard to replace (cultural fit is harder to assess than skills)

The team knowledge they hold is distributed across relationships

The retention strategy:

Recognize and reward their impact beyond individual output (often this means promotion to formal leadership)

Give them opportunities to mentor formally (tech lead, team lead roles)

Involve them in hiring (they’ll help maintain the cultural bar)

Pay them for the value they create across the team, not just their individual contribution

Warning: Don’t confuse cultural carriers with people who are “nice” or “popular” but don’t actually raise performance. The test is: do other people’s outputs improve because of this person’s presence? If yes, they’re a cultural carrier worth retaining. If no, they’re just well-liked.

When to Let People Go (Even Good Performers)

This is the hard part that most managers struggle with: recognizing when letting someone go is actually the right decision, even if they’re contributing value today. These are the patterns where replacement ROI exceeds retention ROI despite the person being above-average.

Scenario 1: Wrong Fit for Future Direction

The company’s direction is changing - new technology, new market, new strategy - and this person’s skills, interests, or working style don’t align with where you’re going.

Examples:

Your best waterfall PM as the company shifts to agile

Your hardware engineer as the company goes cloud-native

Your inside sales specialist as you move upmarket to enterprise

Your individual contributor who’s great at execution but you need builders

Why this is a retention trap:

You’re tempted to keep them because they’re good at what they currently do

But the role is evolving and they’re not evolving with it

You end up either forcing them into a role they’re not suited for (they fail and are miserable) or creating a special role just for them (which is expensive and creates organizational complexity)

The right move:

Have an honest conversation about the direction and the skills needed

Give them 6-12 months to transition skills if they’re motivated to do so

If they’re not motivated or can’t make the shift, help them find a better-fit opportunity

Exit gracefully with severance and, ideally, outplacement support

Why this works:

You free up a seat for someone aligned with the future direction

They find a role where their skills are actually valued

Team sees that you’re serious about the strategic shift

Everyone wins in 12-18 months

Scenario 2: Salary Expectations Exceed Market by 50%+

Sometimes good performers develop salary expectations that are just disconnected from market reality - often because they’ve gotten competing offers at companies that overpay or because they’ve conflated their value at this company with their market value.

The warning signs:

They’re asking for $200K when market for their role is $120K-140K

They think their company-specific knowledge justifies a 50%+ premium

They’ve gotten an inflated offer from a company that’s known for overpaying

They’re anchored on comp from a previous hot job market that’s cooled

Why paying this premium doesn’t work:

Creates massive salary compression issues (how do you justify this to other team members?)

Sets a precedent that threatening to leave gets you off-market comp

They’ll still be unhappy in 12 months when their next “market adjustment” doesn’t come

You could hire two good people for that salary and get more total output

The right move:

Explain the market data transparently

Offer what’s actually market-competitive (maybe 75th percentile)

If they insist on the inflated number, let them take that other offer

Replace them at market rate

Scenario 3: Cultural Drags Despite Good Output

This is the hardest category to act on because the person is technically performing well on paper - hitting their numbers, delivering projects - but they’re creating cultural damage that’s hard to quantify.

What cultural drag looks like:

Creates political drama or camps within the team

Undermines other leaders or initiatives behind the scenes

Takes credit for others’ work, blames others for failures

Spreads negativity or cynicism that’s contagious

Creates an environment where top performers don’t want to stay

Refuses to collaborate, hoards information, sabotages others

Why this is a retention trap:

Their individual output looks good in performance reviews

Exiting them feels unfair because “they’re hitting their numbers”

You tell yourself you can coach them on these behaviors

But the team knows they’re toxic and wonders why you tolerate it

The right move:

Give them direct feedback once about the behavior (not personality)

If it doesn’t change immediately, exit them

Don’t drag it out with PIPs or endless coaching - cultural fit issues rarely improve

Explain to the team (without throwing the person under the bus) that values matter as much as results

What happens after:

Team morale improves almost instantly

Top performers who were considering leaving decide to stay

Collaboration increases, political drama decreases

You wish you’d done it 6 months earlier

The hard truth: One toxic high-performer often drives away 2-3 great team players. The net productivity impact is negative even if their individual output is high.

Scenario 4: Better Opportunity for Them Elsewhere

Sometimes the right retention decision is recognizing that someone has outgrown your organization and the kind thing is to help them leave rather than fight to keep them.

When this applies:

They’ve hit the ceiling in your org and there’s no path up

Their skills have evolved beyond what your company needs

They want experiences (international, different industry, startup) you can’t provide

Their career goals have diverged from where your company is going

Why fighting to keep them often backfires:

You create a special role that doesn’t really fit (”VP of special projects”)

You promote them past their capabilities just to keep them

They stay but are increasingly disengaged and frustrated

They leave in 12-18 months anyway, but now it’s acrimonious

The right move:

Have an honest conversation about their career goals

If you genuinely can’t provide that path, tell them

Help them find the right next opportunity

Exit gracefully, maintain the relationship

They become an evangelist for your company rather than someone who feels held back

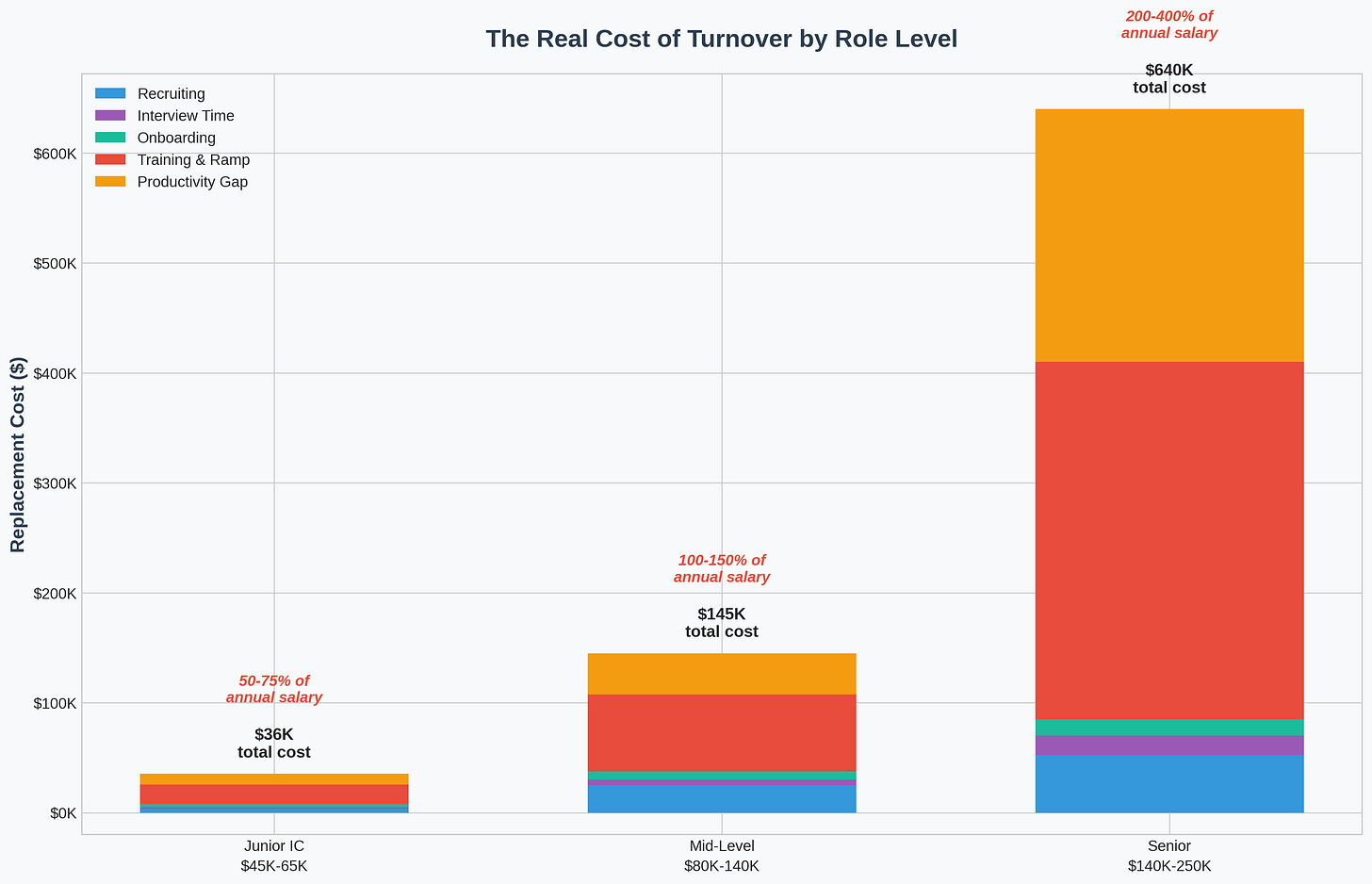

The Real Cost of Turnover (By Role Level)

Let’s get specific about what turnover actually costs. Most managers dramatically underestimate the total cost because they only think about recruiting fees and don’t account for all the hidden costs.

The real cost of replacing someone includes five major components:

Recruiting costs - Agency fees (20-30% of salary), job postings, internal recruiter time, candidate travel

Interview time - Manager hours, team member hours across multiple rounds, reference checks, decision meetings

Onboarding - HR admin, training programs, equipment, access setup, initial coaching

Training and ramp time - The period where the new person is producing at 40-70% capacity while consuming 100%+ of normal management time

Productivity gap - Lost output during the search period, work absorbed by remaining team, projects delayed, opportunities missed

When you add it all up, here’s what replacement actually costs:

Junior roles (individual contributors, <2 years experience): 50-75% of annual salary

Typical range: $22K-49K for a $45K-65K role

Ramp time: 3-6 months to full productivity

Mid-level roles (experienced ICs, first-time managers): 100-150% of annual salary

Typical range: $80K-210K for a $80K-140K role

Ramp time: 6-9 months to full productivity

Senior roles (senior ICs, experienced managers, specialized experts): 200-400% of annual salary

Typical range: $280K-1M for a $140K-250K role

Ramp time: 9-18 months to full productivity

Why senior roles are so expensive to replace:

The costs compound exponentially at senior levels because these people hold institutional knowledge, drive strategic initiatives, maintain critical relationships, and mentor others. When they leave:

Strategic projects stall or fail entirely (opportunity cost in the hundreds of thousands)

Institutional knowledge walks out the door (5-10 years of accumulated wisdom)

Team morale takes a hit (others start questioning the company’s direction)

External stakeholders lose confidence (clients, partners, board members)

You risk a bad hire (30-40% of senior hires don’t work out, forcing you through the cycle again)

This is why a $150K senior person who leaves often costs you $450K-600K in total replacement costs. Fighting hard to retain exceptional senior people almost always makes economic sense - even paying them $200K to stay is cheaper than the replacement scenario.

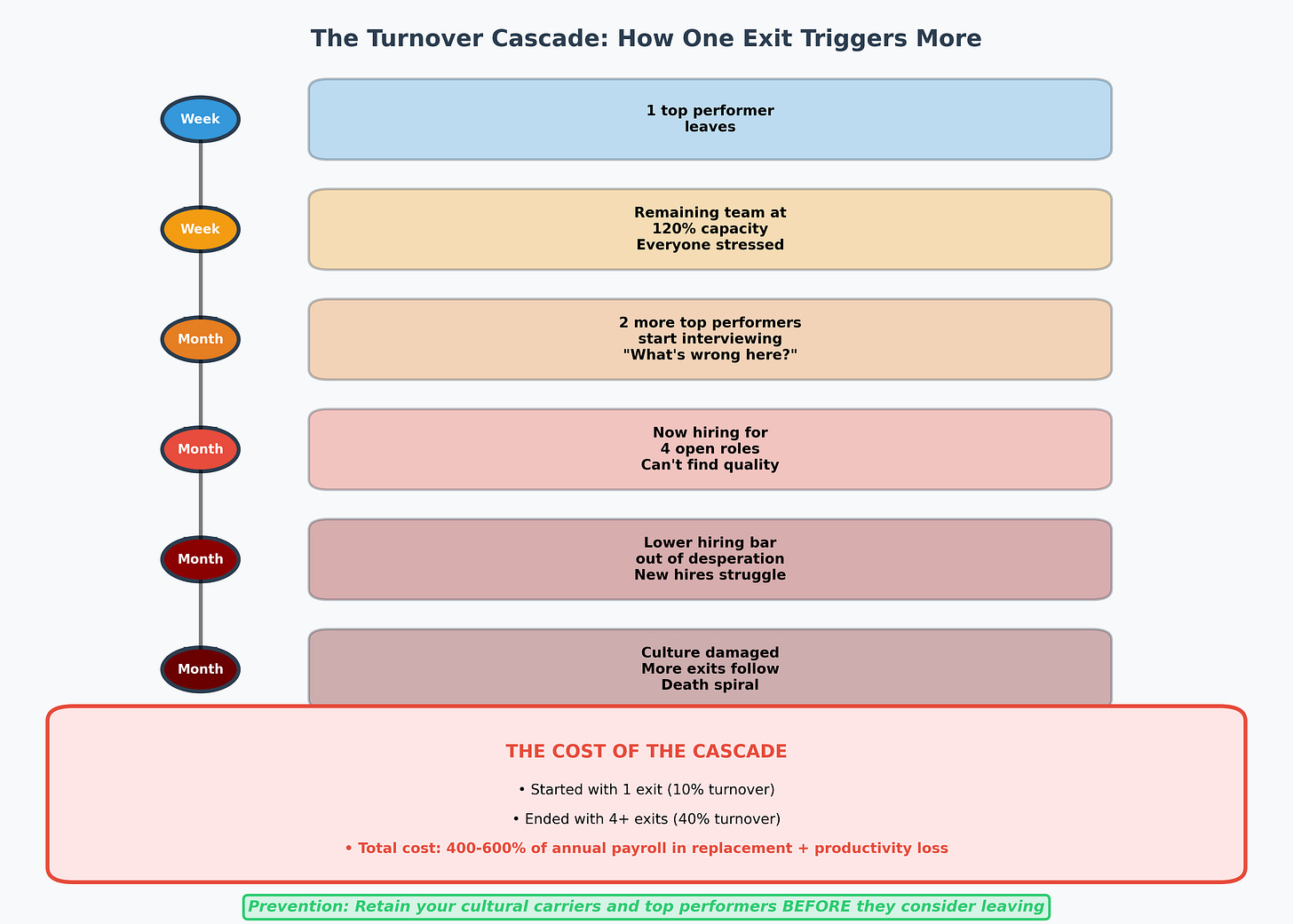

The Compounding Cost of Serial Turnover

Here’s what makes turnover especially expensive: it compounds. When one person leaves, it increases the likelihood that others will leave too.

The turnover cascade:

Strong performer X leaves

Their work gets distributed to remaining team (everyone now at 110-120% capacity)

Team feels overworked and questions company direction

2-3 more people start interviewing

You’re now hiring for 3-4 roles simultaneously

Quality bar drops because you’re desperate to fill seats

New hires aren’t as good, which frustrates remaining top performers

More exits follow

The math: If you have 10% turnover and each exit costs you 150% of salary, that’s a 15% tax on your total payroll. But if that 10% triggers another 10% (cascade effect), now you’re at 30% effective cost. This is why retaining your cultural carriers and top performers is so critical - they’re the ones whose exits trigger cascades.

Common Retention Mistakes (And How to Avoid Them)

Let’s talk about the patterns I see managers repeat that destroy value, burn budget, and still lose people anyway.

Mistake #1: Waiting Until Someone Has an Offer to Invest in Retention

What this looks like:

Someone is a solid performer for 2-3 years at market rate

They get frustrated with lack of progression and start interviewing

They get an offer and tell you they’re leaving

You panic and offer them a 30% raise + promotion to keep them

They accept but are mentally checked out within 6 months

Why this fails:

You’ve signaled that the only way to get ahead is to threaten to leave

Other team members now know the playbook

The person you “retained” is already looking again (they know the first offer won’t be the last)

You’ve created salary compression issues with people who didn’t threaten to leave

You’ve lost their trust - they know you could have paid them fairly before but chose not to

The right approach:

Proactive retention conversations quarterly with top performers

Ask: “What would make you even more excited to be here?”

Invest in development, growth, and compensation before they start looking

Pay them fairly relative to their contribution from the beginning

Don’t wait for market pressure to do the right thing

The economics: Spending an extra $10K/year proactively on a top performer costs you $10K. Waiting until they have an offer and matching costs you $30K + the cultural damage of everyone learning they should interview to get raises.

Mistake #2: Fighting to Keep Everyone (Retention at All Costs)

What this looks like:

Someone announces they’re leaving and you automatically go into panic mode

You don’t ask yourself “should we keep this person?” - you just assume the answer is yes

You match any offer, make any accommodation, create any special arrangement

Your retention budget is exhausted on people who shouldn’t have been retained

Meanwhile your top performers (who aren’t threatening to leave) get nothing

Why this fails:

You’re optimizing for low turnover instead of optimal turnover

You keep mediocre performers at inflated salaries

You create a culture where threatening to leave is the path to advancement

You don’t have budget left for actual top performers

Your team quality slowly degrades as you retain people you should have upgraded

The right approach:

When someone threatens to leave, take 24 hours to think through the retention ROI

Ask: “If they leave and we upgrade this seat, would we be better off in 12 months?”

Fight hard for top 20% performers in hard-to-replace roles

Let go gracefully of everyone else

Use the saved retention budget to invest proactively in your actual best people

The test: If someone tells you they’re leaving, and your honest reaction is relief mixed with guilt, that’s your instinct telling you this is an addition-by-subtraction exit. Listen to it.

Mistake #3: Negotiating with People Who’ve Mentally Checked Out

What this looks like:

Someone gives you notice

You convince them to give you a week to make a counteroffer

You scramble to put together a retention package

They agree to stay

Within 3-6 months they’re checked out and eventually leave anyway

You’ve now lost them twice and paid a premium for the privilege

Why this fails:

By the time someone gives notice, they’ve usually been thinking about leaving for months

The issue is rarely just money - it’s fit, growth, culture, direction

Counteroffers work <20% of the time beyond 12 months

You’ve delayed the inevitable and made it messier

Meanwhile your team knows this person is half-out and morale suffers

The right approach:

When someone gives notice, accept it gracefully 95% of the time

Only counteroffer if: (1) they’re truly top 20%, (2) you can solve the real problem (not just throw money at it), (3) they haven’t fully decided

If you do counteroffer, make it contingent on 2-year commitment with clawback

Otherwise, focus on a smooth transition and maintaining the relationship

The reality: Most counteroffers fail because the decision to leave wasn’t really about money. It was about growth opportunities, culture, direction, or fit. Money can’t fix those things.

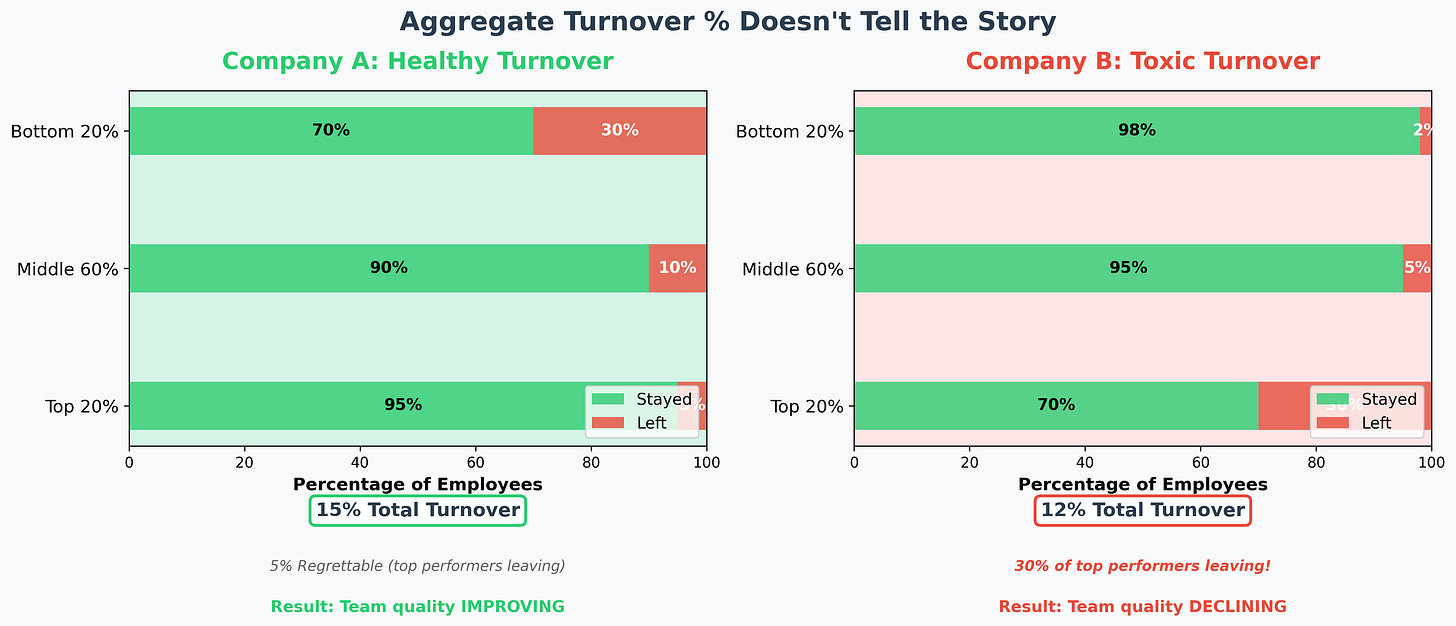

Mistake #4: Treating All Turnover as Equally Bad

What this looks like:

You measure retention rate as a single metric (90% retention = good, 80% = bad)

You don’t distinguish between regrettable and non-regrettable turnover

You’re as upset about losing a bottom 20% performer as a top 20% performer

Your retention initiatives try to keep everyone instead of being selective

Why this fails:

Not all turnover is bad - some is addition by subtraction

Treating all turnover as bad means you invest in retaining people you should be upgrading

You don’t focus your retention investments where they matter most

Your team sees you fighting to keep everyone and wonders if you can’t tell the difference between good and bad performers

The right approach:

Measure regrettable turnover (top 30% performers leaving) separately from non-regrettable

Target should be <5% regrettable turnover, accept 10-20% non-regrettable

Segment your retention strategies: fight for top performers, facilitate exits for bottom performers

Make peace with the fact that optimal turnover is not zero turnover

The math: 15% turnover where you lose only bottom performers is much better than 5% turnover where you’re losing your best people. The aggregate retention rate doesn’t tell you anything about whether you’re keeping the right people.

Mistake #5: Creating Retention Packages for People Who Aren’t Performing

What this looks like:

Someone in Quadrant 4 (low performance + hard to replace) threatens to leave

You panic because “we’ll never find someone with these skills”

You create a retention bonus, special title, accommodation package

They stay but still don’t perform

You’ve now committed budget to retaining someone who’s not adding value

Why this fails:

Retention packages don’t fix performance issues

You’re using retention budget on someone who shouldn’t have a retention package

The team sees you rewarding poor performance and morale drops

You’ve made it even harder to exit them later (golden handcuffs work both ways)

The right approach:

Don’t confuse “hard to replace” with “worth retaining”

If someone isn’t performing, work on performance first

If they improve, then consider retention investments

If they don’t improve, exit them regardless of replacement difficulty

A gap in the role is better than someone underperforming in the role

The principle:** Retention packages are for people who are performing and you want to keep. Not for people who are underperforming and happen to be hard to replace.

The One Thing to Remember

If you forget everything else from this framework, remember this:

Retention is not about minimizing turnover. It’s about maximizing the return on your retention investments by being strategic about which people you fight to keep, which exits you facilitate gracefully, and which situations require difficult conversations about fit.

The math is clear:

Top 20% performers are almost always worth fighting for (replacement cost is 200-400% of salary)

Bottom 20% performers should be exited respectfully (keeping them costs more than replacing them)

The middle 60% requires judgment based on replacement difficulty and future potential

Optimal turnover is not zero turnover—it’s selective turnover that upgrades your team over time

The operational reality is clear:

Companies that retain everyone end up with teams that slowly regress to mediocrity

Companies that accept all turnover lose their best people and institutional knowledge

Companies that optimize retention strategically compound talent quality over time

This framework should give you the structure to make these decisions systematically instead of reactively going forward.

What a weird and wonderful world,